Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, was named in honor of Sir Thomas Brisbane (lived 1773–1860), who was a British soldier and colonial administrator; Sir Thomas was born in Ayrshire, Scotland. He served as Governor of New South Wales at the time when Brisbane was named. Prior to European settlement, Brisbane was occupied by various Aboriginal tribes.

The region was first explored in 1797, when Matthew Flinders made a landing at what is now Woody Point in Redcliffe. A permanent settlement in the region was not founded until half a century later, when New South Welsh Governor Brisbane was requested by Sydney free settlers that the worst convicts be sent elsewhere.

On October 23 1823, Surveyor General John Oxley set out with a party in the cutter “Mermaid” from Sydney to “survey Port Curtis [now Gladstone], Moreton Bay and Port Bowen, with a view to forming convict settlements there”. The party reached Port Curtis on November 5. Oxley suggested that the location was unsuitable for a settlement, since it would be difficult to maintain.

As he approached Point Skirmish into Moreton Bay, he noticed several Indigenous Australians approaching him, led by several white bedraggled timbergetters. The white men turned out to be shipwrecked timbergetters by the names of Thomas Pamphlett, Richard Parsons, John Finnegan and John Thomson who had left Sydney on March 21 of the same year to sail along the coast in search of cedar. They had been living with the Indigenous tribe for seven months.

After meeting with them, Oxley proceeded approximately 100km up what he later named the Brisbane River in honour of the then-Govenor Brisbane. Oxley explored the river as far as what is now the suburb of Goodna in the city of Ipswich, about 20km upstream Brisbane’s central business district. Several places were named by Oxley and his party including Breakfast Creek (at the mouth of which they cooked breakfast), Oxley Creek and Seventeen Mile Rocks.

In 1824, the first convict colony was established at Redcliffe Point under Lieutenant Miller. Meanwhile, Oxley and Allan Cunningham explored further up the Brisbane River in search of water, landing at the present location of North Quay. Only one year later, in 1825, the colony was moved south from Redcliffe to a peninsula on the Brisbane River, site of the present Central Business District, called “Mean-jin” by the local Turrbul inhabitants. The settlement was named “Edenglassie” (in honour of Edinburgh and Glasgow, Scotland) by British pioneers but was subsequently renamed to match the river. The offical population of Brisbane at the end of 1825 was “45 males and 2 females”.

The colony was originally established as a “prison within a prison” – a settlement, deliberately distant from Sydney, to which convicts who reoffended while serving their sentences could be sent as punishment. It soon garnered a reputation, along with Norfolk Island, as being one of the harshest penal settlements in all of New South Wales.

Private settlement near the area was forbidden for many years, and the colony was sluggish in development. As the inflow of new convicts decreased steadily, the population began to decline. In 1838, the area was opened up for free settlement, beginning with a group of Lutheran missionaries from Germany who were granted land in what is now the northside suburb of Nundah. Larger numbers of free settlers in the 1840s took advantage of the abundance of timber in local forests inhabited by humans and wildlife that could be displaced with no legal recourse. Grazing and farming took hold quickly on the fertile land of the coastal plain, and the convict colony was eventually closed.

By 1869 almost all of the Turrbul people had died from gunshot or disease. The few remaining survivors escaped the region with the help of a settler, Tom Petrie, (now associated with the suburb of Petrie in Pine Rivers Shire, north of Brisbane).

Originally the neighbouring city of Ipswich was intended to be the capital of Queensland but Ipswich proved too far inland to allow access by large ships and so Brisbane was chosen as the capital instead. Ipswich as the Capital of Queensland was chosen after Charters Towers in North Queensland. Construction and planning to make Charters Towers the state’s capital was well under way when the Gold Mining boom suddenly ran dry, which shocked and dismayed many people as the estimated reserve of gold was put close to 150 years. Ipswich was then chosen and rejected because of the transportation problems involved; in the 1800′s transportation was a primary consideration in locating many of the Capital cities.

Queensland was formally established as a self-governing colony of Britain separate from New South Wales in 1859. Brisbane was declared the capital, but not until 1902 was it officially designated a city. Severe flooding in the 1890′s devastated the city and destroyed the first of several versions of the Victoria Bridge. Even though gold was discovered north of Brisbane, around Maryborough and Gympie, most of the proceeds went south to Sydney and Melbourne. The city remained an underdeveloped regional outpost, with comparatively little of the classical Victorian architecture that characterized southern cities.

The first railway in Brisbane was built in 1879 when the line from the western interior was extended from Ipswich to Roma Street Station. First horse drawn, then electric Trams operated in Brisbane from 1885 till 1969. Tramway employees stood down for wearing union badges on 18 January, 1912 sparked Australia’s first General strike, the 1912 Brisbane General Strike which lasted for five weeks.

In an effort to prevent overcrowding and control urban development, the Parliament of Queensland passed the Undue Subdivision of Land Prevention Act 1885, resulting in Brisbane and other Queensland cities having very low population densities and covering large areas compared to similar Australian cities.

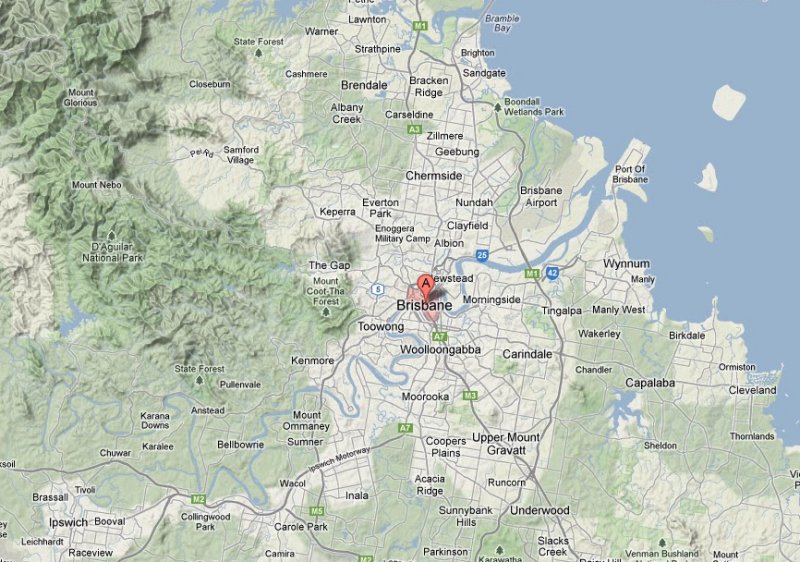

This legislation, together with the advent of efficient public transport in the form of steam trains and electric trams encouraged the spread of the city. Although the initial tram routes reached out into established suburbs such as West End, Fortitude Valley, New Farm and Teneriffe, later extensions and new routes encouraged housing developments in new suburbs, such as the western side of Toowong, Paddington, Ashgrove, Kelvin Grove and Coorparoo. This was a pattern of development to continue through to the 1950′s, with later extensions encouraging new developments around Mt Gravatt, Stafford, Camp Hill and Enoggera. Generally the train lines linked established communities, although the Mitchelton line (later extended to Dayboro, before being cut back to Ferny Grove) did encourage suburban development out as far as Keperra.

Subsequently, with the advent of private transport in the form of cars, land between tram and train routes was developed for settlement, for example Ekibin, Tarragindi, Everton Park, Stafford Heights and Wavell Heights.

In 1924, the City of Brisbane Act was passed by the Queensland Parliament, amalgamating the Cities of Brisbane and South Brisbane; the Towns of Hamilton, Ithaca, Sandgate, Toowong, Windsor and Wynnum; and the Shires of Balmoral, Belmont, Coorparoo, Enoggera, Kedron, Moggill, Sherwood, Stephens, Taringa, Tingalpa, Toombul and Yeerongpilly to form the current City of Greater Brisbane, now known simply as the City of Brisbane, in 1925. To accommodate the new enlarged city council the current Brisbane City Hall was opened in 1930. Many former shire and town halls became the nucleus of Greater Brisbane’s public library network.

Due to Brisbane’s proximity to the South West Pacific Area theatre of World War II (Second World War), the city played a prominent role in the defence of Australia. The city became a temporary home to thousands of Australian and American servicemen. Buildings and institutions around Brisbane were given over to the housing of military personnel as required. The present-day MacArthur Central building became the Pacific headquarters of U.S. General Douglas MacArthur, and the University of Queensland campus at St Lucia was converted to a military barracks for the final three years of the war. Newstead House was also used to house American servicemen during the war.

Brisbane marked the northern point of the “Brisbane Line” – a controversial defence proposal, allegedly formulated by the Menzies government, that would, upon a land invasion of Australia, surrender the entire continent bar the populated coastal strip south of Brisbane to the Japanese.

On November 26 and November 27 1942 rioting broke out between US and Australian servicemen stationed in Brisbane. By the time the violence had been quelled one Australian soldier was dead, and hundreds of Australian and US servicemen were injured along with civilians caught up in the fighting. [1] Hundreds of soldiers were involved in the rioting on both sides. This incident, which was heavily censored at the time and apparently was not reported in the US at all, is known as the Battle of Brisbane.

Immediately after the war, the Brisbane City Council, along with most governments in Australia, found it difficult to raise finances for much-needed repairs and development. Even where funds could be obtained materials were scarce. Adding to these difficulties was the political environment encouraged by some aldermen, led by Archibald Tait, to reduce the city’s rates (land taxes). Ald Tait sucessfully ran on a slogan of “Vote for Tait, he’ll lower the rate.” Rates were indeed lowered, exacerbating Brisbane’s finances.

Although Brisbane’s tram system continued to be expanded, roads and streets remained unsealed. Water supply was limited, although the City Council built, and subsequently extended, the Somerset Dam on the Stanley River. Despite this most residences continued to rely heavily on rainwater stored in tanks.

The limited water supply and lack of funding also meant that despite the rapid increase in the city’s population, little work was done to upgrade the city’s sewage collection, which continued to rely on the collection of nightsoil. Other than the CBD and the innermost suburbs, Brisbane was a city of “thunderboxes” (outdoor toilets) or of septic tanks.

What finances could be garnered by the Council were poured into the construction of Tennyson Powerhouse, and the extension and upgrading of the New Farm Park powerhouse, to meet the growing demands for electricity.

Work continued slowly on the development of a town plan, hampered by the lack of experienced staff and a continual need to play “catch-up” with rapid development. The first town plan was adopted in 1964.

1961 saw the election of Clem Jones as Lord Mayor. Ald Jones, together with the new town clerk J.C. Slaughter sought to fix the long term problems besetting the city. Together they found cost-cutting ways to fix some problems. For example new sewers were laid 4 feet deep and in footpaths, rather than 6 feet deep and under roads. In the short term, “pocket” or local sewerage treatment plants were established around the city in various suburbs to avoid the expense of developing a major treatment plants and major connecting sewers.

They were also fortunate in that finance was becomming less difficult to raise and the city’s rating base had by the 1960′s significantly grown, to the point where revenue streams were sufficient to absorb the considerable capital outlays.

Brisbane has been inundated by four severe floods of the Brisbane River — in 1864, 1893, 1897 and 1974. A comprehensive flood mitigation scheme was instituted for the Brisbane River catchment area in the aftermath of the 1974 flood. Since then the city has remained flood free during unbroken cycles of drought, locust plagues and outbreaks of infectious, insect-born diseases including malaria, Dengue fever and Ross River virus. During this period real estate values in Brisbane have risen 15 fold.

In the 1980s Brisbane came of age as a metropolis in its own right, finally discarding its perceived image as a “big country town” of little importance. The city hosted two important events that attracted international attention – the Commonwealth Games in 1982 and Expo ’88 in 1988. These events coincided with a massive growth in urban development and population in metropolitan Brisbane, a boom that is yet to cease.